[Reposted from 2011, a post that was lost when the Years Of Being blog was destroyed.]

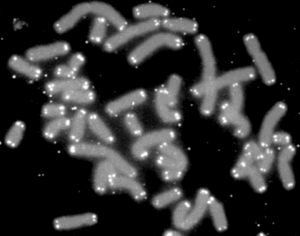

Telomeres

The human telomere. A bit of material at the end of each chromosome. Some have likened a telomere to an aglet, that piece at the end of a shoelace that generally has a bit of plastic on it, making it easier to thread the holes when you lace up your shoes. And just as an aglet over time becomes somewhat frayed, and finally almost totally useless, the telomere sitting at the end of the chromosome “shoelace” gets a little shorter each time a cell divides. Until finally there is no telomere left. But whereas you can keep stuffing the frayed aglet into the eyelet of a shoe and lace it up one more time, when the telomere is consumed, the cell can no longer divide.

It’s “lifetime” is over. Kaput. Dead.

As you yourself will eventually be. Because when, say, the cells of the liver cease replicating, the liver is pretty much left with what it has at that time. And therefore it’s ability to repair itself becomes more and more compromised over time. No more new liver cells, and then when the old ones finally wear out, too bad. Just have to “do more with less”.

And so it goes with all the body’s organs and systems and bones and tissues. Over time, their ability to rejuvenate weakens and abates, and so the body gets less and less flexible and less and less adaptable. And weaker. And the hair grays. And the skin wrinkles.

You age.

And then you die. All because some arbitrary mechanism exists whereby DNA has a built in long-term self-destruct mechanism: the telomeres.

Among scientists who study such things, telomeres are the primary (and obvious) suspects as the agents of aging and death. Most of us consider aging and death pretty much as givens, like taxes. But unlike taxes, which are after all, a pure invention of the human mind, aging and death are inexorable. After all, we essentially have to agree, collectively, or be forced to agree, that such a thing as taxation will be enacted. Death stalks us whether we will or no. It is so ubiquitous, so universal, that the fact of its existence, its raison d’etre, is never questioned. We may substitute eternal spiritual afterlife as some sort of alternative. But the fact that we age and die? No, we fully expect that.

But why? I mean (without trying to be too tongue-in-cheek), what’s the benefit in death? Why should the primary replicative structure that subtends all life have a built-in mechanism that terminates that life after so many revolutions? A moment’s thought should reveal that there really is no particular, inherent, fundamental reason that even begins to make sense. If the telomeres did not get shorter on each replication, the world would be a very different place. Oh, death would still happen. Cut off the oxygen, slice off the head, drop the body off a cliff, death will occur. But not dying from old age, because there would be no old age.

Of course, one can argue that, without telomeres, without a built-in mechanism to kill an individual, then the species would have a much harder time adapting via natural selection. Only when individuals die off do they take their lousy genes with them. Telomeres are perfectly suited to enforce the mechanism of natural selection.

The problem is that this argument is itself a teleological argument. “Telos” is the Greek for “end”. Hence, telomeres are at the end of the chromosomes. A teleological argument is an argument that starts from the end, the “end justifying the beginning”. Natural selection may indeed require telomeres to operate. But need does not constitute cause. I need to make a car payment. That does not cause the money to appear in my back account. Natural selection is, at its root, a completely random process. Just because an animal in the desert would benefit from organs that conserve water will not produce a camel. But if a series of accidental mutations produces an animal that carries water bags in its humps, then natural selection will favor that animal in that environment, and thus we see more camels in the Sahara than hippopotami.

So the fact that natural selection itself “needs” telomeres is not a sufficent reason for them to exist. Furthermore, any mechanism that inherently kills the individual is not a good candiate for a trait that would likely be passed on. In fact, such a mechanism is absolutely counter to the existence of a particular individual. It is the opposite, as far as an individual is concerned.

And in any case, this is not a genetic trait that is “passed on”. It is an integral part of the genetic machine. It precedes and defines the generic machine. Oh, individuals may have longer or shorter telomeres (and the length itself seems to be an inherited genetic trait), but the basic fact of telomeres, and their operation, are part and parcel of the structure of the chromosome. Telomeric activity is inherent.

And here’s a cosmic comic thought: Telomeres may be the most powerful argument ever encountered for some sort of “intelligent design”. But definitely not in the “let’s make man in our image” style of argument usually proposed. It’s more “let’s create this random generation mechanism involving DNA and mutations, and let ‘er rip, and see what it produces. But let’s make sure the life forms that arise will automatically die off, so that evolution will be forced to take place.” It’s not so much God walking through the Garden as it is a monolith descending from the cosmos, ordering the mechanism that subtends life itself to include this automatic “cash in your chips” activity, just so natural selection will operate correctly.

That’s a very spooky form of intelligent design. In fact, it’s almost diabolical, at least from the individual’s perspective. From my perspective, that telomere just downright sucks.

So that’s one aspect of what I call the Telomeric Irony. The fact that telomeres exist at all is cosmic irony of the first degree. The only reason I will die a natural death is not even a defensible reason, unless I postulate a cosmic engineer who arranged it that way. Not exactly the sort of deity I am prone to worship.

But let’s get past the primary irony, the ontological irony implied by their mere existence. Let’s just take that as a given, since there’s not much to do about it, and no profit in bemoaning it. It was Death and Taxes before we knew about telomeres, it’s Death and Taxes now that we do know. So we die. Okay.

Because, really, I don’t think infinite, conscious life is a particularly inviting prospect. Don’t get me wrong, I am in no way ready to cash it in, nor am I the despairing, despondent type. Far from it. I would run just as fast as I could away from that Far Country, I will not go quietly into that dark night. But face it: infinite life is an ego-crushing concept. Even heavenly, spiritual infinite life. My daughter once observed that the prospect of singing Hallelujahs forever was just unbelievably depressing. It’s that idea of our individual consciousness existing without end that is so numbingly oppressive. The idea that this internal monologue, the observer that is ME, would go on, commenting and assimilating and rearranging and THINKING without end, amen, that idea is just so overwhelming as to be horrific. How many times can you sing the Hallelujah Chorus, for God’s sake. Or for Whoever’s?

I think most of us, at an almost unconcious level, think in much more finite terms. “When we’ve been there, 10,000 years, bright shining as the sun”. So begins the final verse of Amazing Grace. “10,000 years.” Gosh, it seems so long. But what if it had said, “ten million years”. Or ten trillion. Or a google’s worth of years. That’s 1 followed by a 100 zeroes worth of years. Chew on that for a bit. Consider what that would really mean. Gad.

The second aspect of the Telomeric Irony is then this: why the hell were we given a mere three score and ten, on average? I mean, talk about arbitrary. Why not a couple of hundred, like a tortoise. Or even a thousand? After a thousand years, I think even the most creative soul that ever perceived and conceived would have exhausted all the possibilities. But seventy? Just seventy? I mean, most humans take five or six decades just to figure out how most of this crap really works. Then (to quote Dave Matthews), it’s “lights out, you up and die”. That is the really grating irony. Death is not that bad of a concept, it can even be deemed necessary, if for no other reason than to make room for everybody else. No, it’s the early exit that sucks. It’s just not commensurate with our consciousness, with the kinds of things we can conceive and invent and make and manipulate. This brief candle is probably the heart of greed and rapaciousness and gluttony and excess. Knowing you’re going to check out 3-4 decades from now doubtless motivates some personalities to start grabbing everthing in sight, and taste, touch, do, try, go: hurry, hurry, hurry!

It is especially pissy when juxtaposed against the thought that some architect put the damn telomeres in there in the first place. Hey, Grand Cosmic Designer! Yes, You. Why the heck didn’t you cut us some slack here? Seventy years might have seemed a decent choice in the Nelolithic when homo sapiens enjoyed 20 good years on average before saber teeth or bear claws or other cave dudes cut him down. Not such a good idea after the people start writing symphonies and invent literature and music and so forth. In fact, pretty much right after we managed to get enough spare time to look in the mirror and recognize that Self who is I, that was when the arbitrary time limit took on its truly tragic aspects.

Arthur C. Clark often wrote about the recurring theme that informed “Childhood’s End” and “2001: A Space Odyssesy”, the idea that humankind was on the cusp of the Next Great Step, symbolized by the enigmatic Star Child that appears at the end of the movie rendition of ”2001.” Perhaps this transition happens soon, perhaps it is happening now. Perhaps the 95% of our DNA currently classified as “junk”, since it does not seem to transcribe anything useful, will suddenly blossom into the Indigo Children of the near future, the Heroes, the Star Children. One can also consider oft-repeated fictional device of the Immortal, a person who, for whatever reasons, lives for millenia, watching the endless parade of history roll by, hiding his eternal nature from those who would be murderously envious. Perhaps there are individuals whose telomeres don’t slough off, and are therefore, for all intents and purposes, immortal.

Perhaps. And perhaps the Indigo Children, when they break out of their cocoons and morph into Destiny and Possibility, perhaps there will likewise be something in that genetic flowering that drastically lengthens those tender little telomeres, extends the neohuman lifetime and retains the vigor of youth. Or else they might interbreed with Immortals.

Because it would be a tragicomic pity to blossom into godlike consciousness and capabilities, and still be constrained to the three score and ten of your forefathers and mothers.

© 2011 Chuck Puckett